|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Nollaig Casey, Chris Newman, Arty McGlynn & Máire Ní Chathasaigh

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Press interviews with Arty McGlynn, Nollaig Casey, Chris Newman and Máire Ní Chathasaigh

|

|

|

|

|

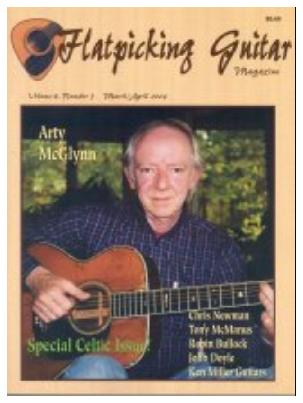

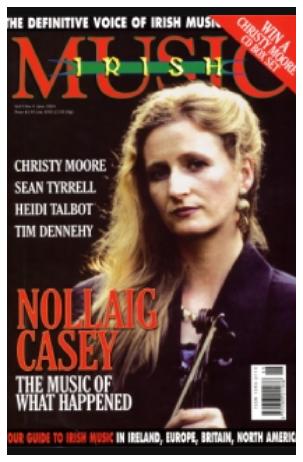

Nollaig, Arty, Máire and Chris have been interviewed many times over the years. On this page you'll find a selection of press interviews: an interview with Arty by Flatpicking Guitar Magazine (he also features on the cover of that issue), an interview with Nollaig by Irish Music Magazine (again, she featured on the cover of that issue) an interview with Chris by Flatpicking Guitar magazine and an interview with Máire by Jakarta-based cultural advocacy organisation Listen to the World. In addition, here's a link to Máire's interview with the Bunbury Mail about the quartet and their 2014 tour of Australia.

|

|

|

|

|

Interview with Arty McGlynn

Flatpicking Guitar Magazine

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Arty McGlynn is to flatpicking traditional Irish music what Doc Watson is to flatpicking American fiddle tunes...

...Like Doc, Arty took an instrument that was primarily used in an accompaniment role and gave it a lead voice. He first did this in a recorded form on his 1979 release McGlynn's Fancy: Arty McGlynn Plays Traditional Irish Music on the Guitar. The recording was immediately hailed as a 'classic in the traditional music world' and as a result Arty became 'the most sought after musician in Ireland.' And, like Doc, Arty continues to create and innovate while remaining true to tradition. Fintan Vallely of the Irish Times recently stated, 'Almost 20 years since he first played this venue (Belfast's Harp Folk Club), McGlynn's picking of tunes was hugely impressive, a terrific demonstration, not only of the impact this player has made to the use of guitar in traditional music, but of the unfazed consistency of his innovation.'

Arty McGlynn has played and recorded with some of Ireland1s most famous individual artists and bands, including Christy Moore, Paul Brady, Donal Lunny, Liam O'Flynn, Planxty, Patrick St, De Dannan, the Chieftains, and the Van Morrison Band, to name a few. He has been, and remains, in high demand as a performer, recording artist, and producer. He is also a 'guitar player's guitar player' on the Irish music scene.

In preparation for this special Celtic guitar issue of Flatpicking Guitar Magazine I approached a number of well known guitarists from England, Ireland, and Scotland and asked who we should feature on the cover of this special issue. The answer in every case was the same, 'Arty McGlynn.'

Although Arty's name is mostly associated with traditional Irish music, his early professional career took him away from the traditional music that he encountered and learned from his family while growing up in Omagh, County Tyrone, Ireland. Arty said,

"There was always music in the house my mother played fiddles, my brothers and father played accordions. Istarted playing accordion when I was about five and played until I was eleven. There was always a banjo in the house and I used to play around on that as well. Then my mother bought me an electric guitar in 1956. That was the explosion of rock and roll and the whole thing. The skiffle thing was all happening."

Recalling his early years playing accordion with his family, Arty said that the best lesson he learned about music came from his father who said, "You are losing time! It doesn't matter if you miss some notes, don't lose time. Even if you have to skip over a few notes, make sure your time ends up the same when you are finished." Arty said, "My father wasn't really a teacher. I learned more from my mother, who was a fiddle player. But that was a very good lesson that he taught me."

When Arty got his first guitar, at about the age of 12, there was only one other guy in town that he knew who played the guitar. He says,

"He was about five years older than me, but he was a very patient type of guy. He could figure stuff out. He could read music. He knew his chords. I used to go to his house and he opened up a lot of doors for me very easily that probably wouldn1t have had the discipline to do myself at that time. I learned a lot from him and I also studied theory with a sax player from Omagh named James O1Niell. He was a fine jazz musician."

At a fairly young age Arty was delving into the playing of jazz greats like Wes Montgomery and Barney Kessel, which he was led to through his earlier interest in Chuck Berry, Jerry Lee Lewis and Gene Vincent.

Arty explained that during the mid-to-late fifties most of the dance bands in Ireland were coming out of the swing era. When he was fifteen he joined a dance band called the Melody Boys and began playing professionally. He says,

"It was a great experience for me because apart from doing the rock and roll stuff at home that I was learning off of records, I had to read charts and play swing chords with the band. It was good experience for a kid. I learned my theory from those bands, but I was always into playing rock and roll."

Although he stopped playing Irish music in about 1955, Arty says,

"I was still always aware of it because it was always in my house. During that time I sort of had a love/ hate relationship with Irish music. Where I went to school there were dancing and music competitions that were very strict and conservative. I fought against all of that and I associated Irish music with all that for a long time. I like the music, I just didn't like the stuff that went along with it."

Arty also explained that during that era Irish music was not arranged in parts, everyone that played in the band played the melody at the same time while someone 'banged away on chords on the piano.' Arty said, "It wasn1t very attractive." He said that it wasn't until Sean O'Riada, of University College, Cork, began to arrange traditional Irish music (late 50s through the 1960s) with defined parts that the music began to change. In Celtic Music: A Complete Guide author June Skinner Sawyers explains that

Prior to O1Riada's ensemble Ceoltoiri Chualann, "traditional music was considered a solo art, except for the popular ceilidh dance bands. Using traditional instruments but with classical-style arrangements, the ensemble incorporated elements of harmony and improvisation‹alien concepts in Irish traditional music." Paddy Moloney, of O'Riada's ensemble, later went on to form the Chieftans, the most famous traditional Irish band. Another traditional band that became very popular in the early seventies as Planxty. Arty said, "Planxty started around 1969 or 70. That was attractive, the stuff that Donal and Andy were doing [bouzouki player Donal Lunny and mandolin player Andy Irvine]. I sort of cocked my ear to that again because they were doing nice arrangements on bouzouki and mandolins and it was a different slant on

Irish music. In the meantime I'd been playing from 1959 in rock bands and show bands five-to-six nights a week."

Arty said that 'out of boredom' in about 1970 he started taking the acoustic guitar out on the road with him on the show band bus and playing tunes to pass the time. He said, "I wanted to get out of that situation. A show band is a very boring place to be after the initial excitement. I decided in the early 70s that I would do session work in Belfast and thought that if I could get the session work built up a bit, I could get off the road."

In about 1977 singer-songwriter Paul Brady, of the Johnstons (late 60s) and Planxty (mid-70s), had come back to Ireland and asked Arty to join his band in 1979. Arty played on Brady's rock debut album Hard Station which was released in 1981. Arty said, "During the time I was doing session work I would lay down a little track after a session." That finally came out as an album in 1979 as McGlynn's Fancy.

Although the album was heralded as a ground breaking recording due to Arty's lead guitar work on traditional Irish tunes, Arty said, "I was amazed at the attention it got because I did not circulate on the Irish circuit at all when I was in show bands. You play six nights a week, so you don't meet anybody when you are going out like that. So when I made the record, I never thought that it would see the light of day. It was just a hobby, really. But it started getting played on radio."

When asked about the role of the guitar in Irish music prior to that time, Arty said, "Part of the thing that put me off about Irish music was that it was very conservative back then. There was no time for guitars or bouzoukis. They were purists, you know?" In fact, Arty said that when he was growing up and playing Irish music at home with his family, there were no guitars at all. Guitars were not a part of Irish music. He points to Paul Brady as one of the first artists who started to incorporate the guitar into Irish music as a rhythm instrument. Arty said, "Paul had been in the states and he came back in around '73 or '74 and joined Planxty. I had known him in the early 60s when he was in college in Dublin and then we started messing around and playing again and I like what he was doing. He was using some open tunings Šlike open G tuning and drop D tuning. I liked that, so I started playing Irish tunes on the guitar around that time. It was Paul who really stimulated me to do it."

The admiration Arty has for Paul Brady is mutual. In the liner notes to Arty and Nollaig Casey's recording Lead the Knave, Paul Brady wrote: "The first time I became aware of Arty McGlynn's talent was back in the sixties when lost in the crowd one night, I enviously watched his fingers cruise the neck of his Gibson 335. Arty McGlynn even then was recognized as one of the best guitar players in Ireland. If, like me, you were an aspiring guitarist, you didn't pass up an opportunity to catch him when he was in town."

Arty continues, "Donal Lunny also started backing tunes on guitar and using different arrangements that hadn't been done before. But in general the guitar was associated with Elvis Presley, and was looked upon as being a 'sexual' instrument, and so it wasn't very popular with Irish musicians. What also happened was that the people who did get guitars thought that they could just sit down and play with a fiddle player. But they didn't know the tunes. They thought, 'Well it is in D, so I can just play in D'. And it was terrible for the musicians, so they would just leave. So guitars got a bad name because of that. It got to the point where traditional musicians would tell guitar players, "look, if you open that case, I'm going to stop playing."

Reflecting on the technical aspects of his playing on McGlynn's Fancy, Arty said, "To me, it was no big deal. I was playing Django stuff, so to play tunes in the first position in D wasn't all that complicated. But I was amazed at the naiveté of people in Ireland, even in the late 70s, who were saying, 'How can you do that on a guitar? How can you play a reel on a guitar.' And I'm saying to them, 'Haven't you ever heard of Joe Pass or Django Reinhardt?' They had obviously never listened to the guitar. There is no big deal there. A little jig on a guitar?"

After McGlynn's Fancy began receiving airplay Arty got a call from Tommy Makem and Liam Clancy and began working with their group. Makem and Clancy (of the Clancy Brothers) had been two of the pioneers of Irish folk music in the 1960s and performed to sold-out theaters all over Ireland. Arty said, "It was fantastic because it meant that I could still do my studio work and then work for a season in Ireland, two weeks at a theater in Dulbin, two weeks at a theater in Cork, and three weeks touring the country in the summer time. I was making really good money that I had never dreamt of, that I could never make in a show band. I was off stage at ten o'clock every night and playing with people that I really liked. Myself and a fiddle player would sit on stools behind Liam and Tommy backing them up. But then we would get to also go out front and do a solo spot, play a jig or something. That was in 1980."

While Arty did quite well playing with Clancy and Makem, the residual benefits that he gleaned from the success of his solo album did not stop there. In 1982 he got a call from Van Morrison and was asked to join the Van Morrison band. He spent seven years with Morrison's band, performing live and recording on both electric and acoustic guitars. Additionally, since Morrison's band did not work steadily, Arty played with a

traditional Irish band called Patrick Street (founded in 1986 and featuring fiddler Kevin Burke).

After seven years playing with both Van Morrison and Patrick Street, the road began to become a grid again and Arty returned to studio work. Arty said, "I'm not very good on the road. I loved the music, but I didn't like the grind. When you are out on a fast moving seven week tour, after three weeks you don't even know what day it is."

In 1989 Arty recorded an album with his wife, fiddler Nollaig Casey, and the two began to do touring as a duo. In 1990 they were awarded the Belfast Telegraph Entertainment Media and Arts Award for excellence in the field of Folk Music. Around that same time he also started working with piper Liam O'Flynn. To date he is still touring with both Nollaig and O'Flynn and he also keeps himself busy with studio work. As a composer, Arty has composed music for several television documentaries and together

with Nollaig arranged and played music for the sound track of the Irish feature film Moondance as well as Hear My Song, in which they also made an appearance. More recently Arty and Nollaig played on the sound track of the film Waking Ned Devine where the music was composed by Shaun Davey.

In addition to being a talented performer and composer, Arty is also a highly respected producer. The album Barking Mad by the group Four Men & A Dog, which Arty produced, was voted Folk Album of the year by Folk Roots Magazine. He produced Christy Hennessy's album, The Rehearsal, which remained in the Irish charts continuously for eighteen months and also collaborated with Frances Black on her first two solo albums, Talk to Me and The Sky Road, both of which have topped the charts in Ireland and have been critically received in the UK and America.

Arty McGlynn started his life surrounded by traditional Irish music and then moved on to play rock, swing, and jazz on guitar for more than 20 years before going back to his roots. When asked about the technical aspects of playing these various styles of music, Arty said, "I just impose myself on it. I am not too concerned about what the tradition was. I suppose that when I am playing with Liam O'Flynn I play a little different than when I am playing with Frankie Gavin, for instance. Liam is a very straight traditional player and pipes are very modal or very melodic. He plays very old tunes that are modal and so I use the guitar more in a modal percussive form. But when I play with Frankie Gavin or Nollaig, they play different stuff and they don't mind if I stick in a diminished chords, or whatever. So Irish music has changed in that way. Other people are doing that also. If the melody lends itself to a certain chord progression, then why not do it? I don't have any set rules. But at the same time there are certain things that I wouldn't dream of doing. I try to play what fits."

In his book, Accompanying Irish Music on Guitar (distributed in the US by Mel Bay Publications) author Frank Kilkelly has this to say about Arty's rhythm style, "In accompanying, his style is first and foremost rhythmic. He uses primarily dropped D tuning and in his playing you can hear a percussive, crispy top end, as well as a beefy bass sound."

Rhythmically, for traditional Irish music, Arty likes to use a drop D modal tuning so that he gets four D notes when playing a D chord. When playing a G chord, he rarely plays the third (B note). In general, when playing with a piper, he likes to get a percussive rhythm, use passing tones and employ droning notes. But he says, "Different people want you to play different stuff. A lot of people play it with different ideas, so it will depend on who you are playing with." Since the guitar is not a traditional instrument in Irish music, Arty feels that the guitar player is not so much bound by a traditional way of playing the instrument in the context of traditional music, so there is some flexibility and free range of expression that is afforded the guitar. Arty adds, "You have to know what people like and don't like. In Ireland today it is very diverse."

Regarding lead playing for Irish music Arty says, "I think that Irish music sits very well on the guitar in standard tuning. Everything falls nicely in a four fret area of the fingerboard. And I find that if you use drop D, it is a lot easier than using DADGAD where you are using open strings. In DADGAD it is harder to get rolling. The hardest part is getting your small finger to work all the time. But it is not complicated music to play." Arty used Drop D tuning for all of the tunes on McGlynn's Fancy. He said, "Drop D is ideal for Irish music."

When Americans who grew up playing bluegrass and American folk music attempt to play Irish tunes, the hardest part to capture is the rhythm. Arty said, "It is a weird thing. If I hear Americans, or even English people playing Irish music, there is some little thing different about the rhythm. At the same time, if you hear us guys trying to play bluegrass music, there is something missing as well. I'm not sure what that thing is. There are some bands at home that are really good at playing bluegrass music, but there is something in the time that is missing. I don't know - I think that maybe it comes from the dancing. I think you have to see people dancing and hear the rhythms of the feet. Dancers are incredible. If you go down to Kerry and see people dance sets, the rhythms they do with their feet are incredible. It is a pretty uplifting thing. It is fantastic to play for dancers. You see these people moving and you get feedback off of it."

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Interview with Nollaig Casey for

Irish Music Magazine

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Interview with Chris Newman

Flatpicking Guitar Magazine

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

"When I first heard Chris Newman play the guitar in a concert with his musical partner, Irish harpist Máire Ní Chathasaigh, about two years ago I was stunned. He moved around the fingerboard with tremendous fluidity and ease. He played phrases that were totally foreign to my ear, and thus extremely captivating. I remember, in my guitar player's brain, watching him play and thinking how complex his playing seemed. I was thinking, 'I would never be able to do that!' Yet, at the same time there was such simplicity, elegance, and tastefulness to the music he was making that it boggled my mind. Chris is one of those rare players that have a very high degree of technical skill and proficiency, yet remain extremely musical and tasteful.

Raised in the North of England, Yorkshire, it was sibling rivalry that brought Chris his first guitar when he was just five years old. He recalls, "I have a brother who is ten years older than me. In the 50s he was into Buddy Holly and skiffle, which was a big thing in England at the time. He got a guitar for his birthday. His birthday is in September and mine is in October. After he got this guitar, I badgered my parents and said, 'I want one, I want one.' I got a little guitar, that I still remember quite well."

Initially Chris learned everything 'second hand' from his brother. Both he and his brother were playing nylon string acoustic guitars. Chris said, "He was always into acoustic stuff. Neither one of us have either been into electric stuff that much. He was old enough to go to the folk clubs, so he would go there and come back with all of the things that he had sort of memorized. And then I would learn them off of him." Other than a very short 'electric phase' when he was 16 or 17 years old, Chris has always played the acoustic guitar.

When Chris first started he learned to play fingerstyle with his thumb and three fingers (no finger picks). But he says, "I was also sort of playing a flatpick style, but without a flatpick. I would put my thumb behind my index finger and I used the nail of my index finger to pick with. But I was always breaking my nail, even on nylon stringed guitars. It wasn't until I was about 15 years old that a friend at school said, 'You know I think you can get a thing that you can hold.' I didn't know. That weekend I went to the music store and they had this big tray of plectrums. I bought one of those and I have not put it down since. I hardly ever play fingerstyle now."

When asked about his early influences, Chris said, "I remember that there were two records that I got that I sat down and completely ripped off. One was by a guy named Davey Graham and it was an album called Folk, Blues and Beyond. Bearing in mind when it was made, it is just a fantastic record. I still have it. I remember listening to that and saying 'Wow, this is it!' The other record was Down Home by Chet Atkins, which my sister bought me for my tenth birthday."

In addition to learning the fingerstyle licks on these two albums, Chris said that he was a huge Beatles fan. He remembers, "The new Beatles records were always released on a Friday. I'd save up my pocket money, buy the record on Saturday, and have learned the tunes by Sunday. That is what I used to do. So, a lot of the guitar solos that I learned on my nylon string guitar using my index fingernail as a flatpick were George Harrison solos from Beatles records."

A little while after learning how to play with an actual pick, Chris got his first steel string guitar. He said, "That made a big difference. And it wasn't too far after that that I heard Clarence White. I heard him on a record and I didn't have any idea who he was. I was playing with a band, actually, and we were playing in this nightclub in the north of England. They decided that they were going to put on acoustic bands every once in a while. I was playing with this group and the DJ there, rather than playing a rock and roll track at the end of the night put on this acoustic record that someone had given him. It was actually Don't Give Up Your Day Job. The song he played was Huckleberry Hornpipe. I remember it like it was yesterday. I was packing up the gear and I suddenly heard this fiddle playing. I thought 'Well, that is nice.' Then all of the sudden came Clarence's solo. I thought 'What on earth is this!' I had never heard anything like it in my life. I went over to the DJ and said 'What is that?' He said, 'It's this thing here' and he actually gave me the record. I still have it."

Chris took the record home and started learning Clarence White solos, starting with Huckleberry Hornpipe. He played the recording for a friend of his who he knew had a great record collection. His friend was not only familiar with Clarence, but had several Kentucky Colonels recordings. He also told Chris that he ought to listen 'to this guy called Doc Watson.' Chris said, "I though this was fantastic. There was something going on in America that I ought to know about! My friend said, 'Well, while your at it...' and he started pulling out records by Norman Blake and all these people that I had never heard of. It was amazing. He made me a load of cassettes and for ages I would listen to these tapes and it was always something stupendous. I heard the Clarence White recording and thought, 'this guy is really one off.' Then I found out that there really were a ton of these guys out there and that it was quite a thing [laughs]."

Chris has never 'had a real job,' having always made his living playing the guitar. When asked about the kind of music that he has played, he said, "It has been a variety with a capital V." He has done everything from folk, blues, jazz, swing, to commercial music. He has backed up everyone from commercial singers, to comedians, to Celtic performers, to bluegrass fiddler Richard Greene and played in small clubs to huge theaters.

Although Chris achieved a great deal of success playing the guitar professionally during the early part of his career, in about 1985 he reach a point where he decided 'he'd rather play interesting music than pursue interesting pay checks.' He immersed himself in traditional Irish and Scottish music and began touring with Irish harpist Máire Ní Chathasaigh in 1988. Chris said that he discovered Celtic music in very much the same way he discovered Clarence White and bluegrass. He remembers, "I was playing in a bar in Belgium in the seventies and during the break a guy put on a record on the house system and it was this fantastic music. It was an Irish band called Planxty. It was the first time I'd heard Irish music played in that way. I went on and bought the records and started playing the tunes. So, I'd been playing Irish music along with the records, but never playing out. When I started with Máire it involved an enormous amount of work for me to get the style nailed. There is nothing particularly complicated about the tunes, but all of the triplets and ornaments are tough to get right. It is question of feeling your way. You have to know where to put the triplets, cuts, and rolls to give it the right feel. It is really a bit of a minefield."

Because the 'feel' of the music is not something that can be written down and studied through a book, Chris said that he had to listen to a lot of flute and fiddle players. He said, "There is a great recording made by a lady named Mary Bergin who is just the greatest tin whistle player on the planet. I couldn't believe the range of different sounds coming out of this tin whistle. What I did was record this album at 15 ips and then slowed it down to seven-half, then three and three quarters. That way I could dissect the ornaments. I then tried to adapt that to guitar. Of course, working with Máire was great because she knows that stuff inside out and backwards. She'd say, "No, not there!" I'd say, "Why not?" She'd say, "I don't know. You just shouldn't." [laughs]

When Chris and Máire first began working together, they started with her repertoire. She made a tape, and Chris learned the tunes. He says that he listened to the tape over and over and over and learned how to adapt her harp tunes to the guitar. Since then he says that they later began to incorporate other kinds of music, like swing jazz, that made her work a bit harder to adapt to the harp. Today Chris and Máire's repertoire incorporates a wide variety of music from swing, to bluegrass, to Irish and Scottish music. They continue to tour extensively in both Europe and the United States."

"Because Chris did not start out his musical career playing Irish music, and because he had such a wide and diverse background prior to playing Irish music, Flatpicking Guitar Magazine conducted the following interview with Chris regarding the technical aspects of learning Irish music on guitar.

FGM: What would you recommend to flatpickers who wanted to incorporate more Irish music into their playing style?

CN: To be honest, the first thing you do is just listen, and don't try to listen to just guitar players because there aren't that many. Listen to flute players, fiddle players, and harp players. The next thing they could do is to enrol in some kind of summer school like the Milwaukee Irish Fest Summer School or the Gaelic Roots at Boston College.

FGM: I know that you have taught at these schools yourself. What kind of things do you teach and what kind of players do you find are attending your classes?

CN: I had a half a dozen people in my group and they were all intermediate to advanced players. They were all pretty decent players, playing with flatpicks and coming from the bluegrass end of things. They wanted to learn how to apply what they do into the Irish/Scottish context. We spent a lot of time working on the rhythm and working to learn where you should put the triplet and where you shouldn't put it.

FGM: Do you find that people coming from a bluegrass context have trouble getting into the rhythm of Irish music?

CN: They very often have trouble with jigs. Reels are similar to something like Blackberry Blossom so they don't usually have trouble with reels. But when you get them started on 6/8 tunes or 9/8 tunes they have a lot of trouble just getting their head around the idea. It is just a different thing.

FGM: Is there a way that you have found that helps students overcome that difficulty?

CN: Just simply by example. Just getting them playing it. Sooner or later the penny drops. You see people struggling and trying really hard and all of the sudden it is like "Ahh!" Once you get the rhythm right with the right hand, when it comes to playing the tunes it actually becomes easy and where you put all the ornaments will become more evident if you have got the rhythm right in the first place. If you try and learn the tunes with all of the ornaments before you get the rhythm right, you are banging your head against a wall.

When I do these classes I spend a lot of time doing straight technical stuff as well. I know my left hand technique is pretty good, but I know that there are lots of ways that I can improve it. One thing I can do, within five minutes of watching someone, is to tell him or her 'what you really should be working on is this.'

fGM: Do you spend time in the workshops watching the students play and then offering some suggestions regarding their technique?

CN: Absolutely. If you have 25 people in a group it is harder to do that. But I will try to do it whenever I can.

FGM: Tell us about your instructional book.

CN: There are a lot of technical exercises in there. It is aimed at the intermediate to advanced level student. The exercises have the dots and tab and under the tab I also included the fingerings. That is the thing that took me the most time, but it was important because a lot of these tunes, especially the Scottish tunes, have got fantastic jumps, like three octave arpeggios. If you finger them properly, they are not particularly difficult, but if you don't finger them properly you've got no chance at all.

FGM: Is the book all Irish and Scottish music?

CN: No, quite a lot of the tunes I made up myself. It originally started out as an aid to workshops so that I could have some hardcopy to give out to people for the technical stuff. Then someone suggested that I write some tunes out as well.

FGM: When you say 'technical stuff,' what are you referring to?

CN: Finger exercises, loads and loads of them - mostly left hand positioning things because that is where people generally fall down. I used to work with a guitar player years ago, we did little swing jazz gigs together. He was a really good singer and a decent player. He was a very musical player and had great ideas for solos, but he could never play them because he didn't have the technical facility. It was really sad because I¹d be sitting with him and we'd swap leads and he'd play some solo. You could see where he was going and it was really nice, but then it would just fall down. I used to say to him, "If you would just spend a little bit of time on technique anything you want to play is going to be possible."

I don't want you to get the impression that all I am concerned with is technique, but without the basic technique you will do nothing. With this pal of mine it was really sad because it is really easy to teach someone technique, there is nothing magical about it, you basically sit down and just do it and you will improve. But it is almost impossible to teach someone how to be musical. You get people that are fantastic technicians, they can play anything, but they are boring players. It is clean as a whistle, but it is boring. I can think of a million people I've heard like that. This pal of mine was a fantastically musical player, which is the tough bit, but he didn't have the technical ability. I used to say, "You really should do it. It is criminal not to!" He'd say, "Well I can't be bothered with technique" and so he'd stumble away. It is a real shame.

FGM: What would you describe as the difference between Irish tunes and Scottish tunes?

CN: Not huge actually. There are certain types of tunes, like strathspeys, that appear in Scotland and not in Ireland. It all comes down to the ornamentation. The Irish tunes tend to be more heavily ornamented. But even then, that is a generalization because it depends on which part of Ireland you are talking about. There is a definite difference in say people from Donegal and people from Clare. The further north you get in Ireland, the more like Scottish music it becomes, which is not really surprising.

FGM: When you talk about knowing when to use the ornamentation and when not to use the ornamentation, does that come down to an experience and feel thing?

CN: Exactly. As far as I'm aware, no one has ever written it down. For me I had a good mentor in Máire because we'd be sitting at home practicing something and she'd say, "No, you can¹t do that!" The first few times I'd say, "Well, why not?" After a while you can sort of just tell when it is right. I would recommend that anyone interested in learning that sort of thing listen to fiddle players and flute players.

The other thing I tell people at workshops is that the guitar is fairly new to all this. I mean it is a relatively recent addition. It isn"t a traditional instrument. A guitar player's role in that kind of thing is really as a rhythm instrument first and a harmonic instrument second.

I have played with a lot of fiddle players and flute players and I know full well that if a tune is in D, for example, and you start the B part in D or if you start it in Bm and then turn it around different ways depending on where the melody is, the person you are accompanying will not care one hoot. But if you get the rhythm wrong, they will go completely nuts and absolutely hate it. As long as they have that strong rhythm, that is all they are interested in. To evidence this you only have to listen to any recordings made in the 1920s and 1930s by fiddle players like James Morrison or Michel Coleman. They made these incredible fiddle recordings but they were always accompanied by the worst piano player that you have ever heard in your life. But all they wanted behind them was this very percussive 'bash-crash' on the piano. They couldn't care less that the guy was completely playing the wrong chords. You listen to any recordings from that time period and you will find Hapless Harry on the piano! It will just make your teeth ache.

FGM: Since there are not too many lead guitar players in Irish and Scottish music, do you find that other musicians will typically want you to stay in a rhythm role when you get together to jam?

CN: Absolutely. It is one of the reasons I don't play sessions in pubs and things like that. Sessions in pubs on guitar playing Irish and Scottish music is the most boring job in the world. I've got no objection at all to playing rhythm all night. I actually enjoy doing that. But playing rhythm to eight fiddle players who are all trying to play louder than you, I can't be bothered. I hate all that and avoid it like the plague. But in a good situation with a couple of other musicians, especially if you are the only guitar or only chord player there, is great fun.

FGM: In terms of lead guitar work in the Irish music genre, who would you recommend that people listen to?

CN: Arty McGlynn is somebody you really ought to listen to because he has been doing it for a long time and he is a terrific player. He really is very good. He has been on a million records.

If you have the opportunity to listen to Chris Newman play the guitar live or on CD, you ought to treat yourself to it. He is also a talented instructor. His book of tunes, tips and technical advice Adventures with a Flatpick was published by Old Bridge Music in 2001. He is principal guitar tutor to Newcastle University's Folk Music degree course and is much in demand at summer schools: within the last couple of years he has been a guitar instructor at Steve Kaufman's Flatpicking Kamp in Maryville, Tennessee, at Milwaukee Irish Fest Summer School and at Boston College's famed Gaelic Roots."

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Interview with Máire Ní Chathasaigh for Listen to the World

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Being called “Virtuosic, fascinating, dramatic, original, inspired, gloriously adventurous, dazzling, brilliant, stunning, impassioned, electrifying, bewitching, moving, achingly beautiful, influential, revered, unique...” by well-respected media such as The Times, The Daily Telegraph, The Guardian, The Irish Times, The Scotsman, and Folk Roots, or “the most interesting and original player of the Irish harp today” by the late Derek Bell—Northern Irish harpist virtuoso—should already speak enough of a musician. Máire Ni Chathasaigh is certainly one of Ireland’s most influential harpers of our time.

Born 1956 in Cork City, Ireland, Máire was familiar with and interested in music since a very young age. She started from playing the piano at the age of six, the violin when she was ten, and finally the harp at the age of eleven. And having a self-conviction as a full-time professional harper in times like now—instead of any other ‘popular’ instrument—has certainly made her a true artist. She also has earned recognitions such as won a first prize in All-Ireland and Pan-Celtic Harp Competitions on a number of occasions, and received Irish music's most prestigious award, that of Traditional Musician of the Year - Gradam Cheoil TG4 - "for the excellence and pioneering force of her music, the remarkable growth she has brought to the music of the harp and for the positive influence she has had on the young generation of harpers” in 2001.

Now once again, we are proudly pleased to present you this interview session with one remarkable musician, yet a very humble woman.

LTTW: First of all, we’d like to know a bit of your background. At what age did you get interested in (playing) music? And at what age do you decide that music is your thing?

Máire: I can’t remember a time when I wasn’t interested in music. My mother tells me that I could sing before I could walk! I’ve therefore been singing since I was tiny. I started to play the piano when I was six, the violin when I was ten and the harp when I was eleven.

When at school, I was interested in everything and studied as wide a range of subjects as I possibly could. I was very fortunate that the school facilitated this, as Irish schools these days would be far too concerned with the accumulation of the maximum number of points towards university entrance to allow me to get such a broad exposure to so many diverse disciplines. I was accepted into the Medical School in University College Cork, but changed my mind on the day of registration when I realised that medical studies would leave very little time for playing music! I decided upon Celtic Studies – the study of Irish, Welsh and early Irish history – instead. After completion of a post-graduate teaching diploma, I embarked on a music degree, but after one year of this my parents “suggested” that I might like to get a job! I taught in a second-level school for three years, during which time I became convinced that the creative life was for me not a choice but a necessity. I therefore resigned from what was a very well-paid position and embarked on the insecure but rewarding career of a professional musician.

Where did you have your musical training?

I was fortunate to grow up playing both traditional Irish music and classical music in parallel – it has been a great advantage in life to have the ability both to learn by ear and to sight-read. My earliest musical training was provided by my mother. Traditional music education was provided within the family and through membership of the Cork Pipers’ Club. Classical music education on piano was provided by a private teacher, followed by teaching in the Cork Municipal School of Music. Good harp teaching was very hard to find outside of Dublin at that time, so I had to make do with rudimentary teaching from a lady who taught singing to harp accompaniment. I wanted to be able to play traditional Irish dance music on the harp – tunes that I had been playing on the tin whistle and fiddle – so during my teens I developed the special techniques necessary to perform it in an authentic-sounding style, which I still use to this day. I didn’t get “proper” harp tuition until I was 21, when a wonderful pedal harpist called Denise Kelly came to Cork to teach at the SchoolMusic. The great grounding which she gave me in classical harping enabled me to refine and polish my approach to the traditional music I really wanted to play of.

OK, now in the subject of Celtic music; Celtic music is found in many areas across Europe, from Spain, France, England, Wales, Scotland to Ireland. What is the common denominator(s) among them, and what are the unique features of each?

Linguistically, the Celtic languages can be divided into two branches: P-Celtic and Q-Celtic. The languages currently spoken in Ireland and the Highlands of Scotland, and in the past in the Isle of Man, belong to the Q-Celtic branch and are closely related. Welsh, Cornish and Breton belong to the P-Celtic branch and are closely related. Though there would be no mutual comprehension between the speakers of Irish and Welsh, for example, the languages when examined are similar in grammar and syntax. The civilisation of medieval Wales was however similar to that of Ireland in social organisation, literature, myth and legend and in the primacy of the harp in musical expression.

Irish and Scottish musical traditions are closely related, but are very different to Welsh, Cornish and Breton musical traditions – certainly in the form in which they’ve survived into modern times. There are no obvious common denominators.

So, strictly speaking, one can speak of Pan-Celtic language, culture, civilisation, art – but not of a Pan-Celtic musical language.

In the music market, Celtic is one of the most well-known among the world’s roots music with Latin and African as perhaps the main “competitors”. How do you think Celtic music reaches that level in the world?

Even though “Celtic” is not a good or accurate label artistically or historically, as a commercial construct it has been inspired! It’s the best marketing wheeze ever thought up by a record company.

What does Celtic music means to its people? And what does it mean to you personally?

I can only talk about Irish music, which is immensely important to Irish people and intimately bound up with our sense of self. It is hugely important to me personally and is the conduit through which I choose to express myself artistically.

What kind of influence and/or contribution do you think that Celtic music has given to the world of music?

It has a special aesthetic that even in diluted form sparks the imagination of so many people. Musical languages, like languages, encapsulate and represent the spirit of a people and the greater the number of them that flourish, the more they enrich us all. It’s fascinating to see how our particular musical language has moved from a peripheral and endangered position to a prominent one. I’m sure practitioners of currently obscure forms of music will be heartened by this and will be emboldened to introduce themselves to the wider musical world…

There are quite a few women in Celtic music, but only a handful playing the Celtic Harp that includes you of course. Why is that? What made you decide to take on the harp?

My mother tells me that I’d always wanted to play the harp (though I have no recollection of this), so therefore they bought me one when the opportunity arose. I was eleven at the time.

There are now lots of female harpers in Ireland, but only a handful who play professionally.

How different is the Celtic harp compare to other harps, physically? Does it require specific playing techniques as well?

There isn’t really such a thing as a Celtic Harp, historically speaking. A very specific type of harp – usually referred to as the Ancient Irish Harp - was played in Ireland and Scotland for over a thousand years, until the beginning of the nineteenth century. It had several unique features: its forepillar had a pronounced curve and was T-shaped in section; its soundbox was hollowed out of one piece of solid willow attached to a soundboard; it was strung with brass and played with long nails; it was held on the left shoulder; the melody was played with the left hand and the accompaniment with the right; since it was very reverberant, the harpers used very complex stopping techniques to shape phrases. At the beginning of the nineteenth century, this harp was replaced by what is often called the Neo-Irish Harp. This looked superficially like the old Irish harp in that it had a curved forepillar, but it was constructed in a modern manner and played with the pads of the fingers and is the harp, with the addition of modern refinements, that we still play today. It is the harp people normally mean when they refer to the Celtic Harp.

The Welsh harp, by contrast, was always physically very different, and still is so today, though it too was played on the left shoulder.

The Irish/Scottish harp in itself does not require specific performance techniques. However, the stylistically correct performance of Irish dance music does require the use of specific techniques. The techniques I developed for this purpose in the 1970s – there had hitherto been no tradition of dance music performance on the Irish harp - have since then been widely adopted and adapted.

Music in general has transformed into a subject that is merely treated as entertaining and income generating activity. Its other roles and functions, along with its ritual side, continue to disappear. Does this happen to Celtic music as well? Shall musicians and societies accept this change as the future way of looking at music?

Traditional Irish music’s “other roles and functions, along with its ritual side” do seem to be “continuing to disappear”. A number of older musicians in Ireland feel despondent about this change, which from their point of view dates from the creation of the “Celtic Music” marketing brand and the subsumation of Irish music into that. I am much more optimistic, however. I know from personal experience that it is possible to be a professional musician (i.e., “entertain and generate income”) and be true to oneself artistically. It’s unfortunately the case that many musicians for whom commercial success is of over-riding importance do abandon any ambition to touch the heart – with the result that music which is heavily hyped and expensively marketed tends so often to lack soul. But I have a lot of faith in people’s capacity to be moved by music and am constantly amazed by it. Music is the most abstract of all art forms, while at the same time being the most emotionally transfixing. I know that certain 17th century Irish harp airs have the capacity to pierce the heart of the most unpromising audience. Such moments can’t be faked or forced and are what make performance so endlessly rewarding.

We must never accept the commodification of music. As artists we must make common cause with and draw strength from others with the same ethic and world view - and remember that the environmental movement was once considered to be hopelessly romantic and impractical!

Fame and fortune also seem to replace passion as the instrument in measuring the “success” of an artist. How do you reply to this matter?

To me, passion is all-important.

How do the young in UK perceives and (un)appreciates Celtic music?

The young in England are generally speaking uninterested in Celtic music. Large numbers of older people like it very much, I’m happy to say, as our concerts in England are usually very well-attended! They are however perhaps not so emotionally attached to it, as England is not a Celtic country. A good percentage of the young in Celtic countries like Scotland and Ireland are very interested and engaged with the music.

Roots music such as Celtic is very much associated with acoustic instruments. Do the growing use of electric instruments and digitalization affect the acoustic features of Celtic music?

I don’t think that the use of electric instruments in any way affects the essence of the music. The equating of “acoustic” with “authentic” is to me a complete red herring. I myself use an electro-acoustic Camac harp in my duo performances with Chris – the harp sounds the same as it does acoustically, only louder! An instrument is just a vehicle which conveys musical thought and feeling and the fetishisation of its acoustic properties by those I dub “acoustic fundamentalists” is to me simply wrong-headed, and largely to miss the point of music…

You have travelled distances to perform, and have had many chances in getting acquainted with music of other cultures. Are there any of them that inspire or impress you more than the others? And why?

Even the most cheerful Irish music often has a melancholy undertow: I love this duality of mood in music, so am naturally attracted to other music which shares these characteristics – Swedish, Old-Time American, Eastern European, Middle- and Far-Eastern… Traditional African music has a gentle, limpid quality that is immensely attractive.

Who influence and/or inspire you the most, and why them?

So many things inspire me – not just music, but poetry, art… I’ve always been drawn to the music of Bach: so intricate and perfectly balanced. In terms of traditional music, I’ve always loved the singing of Máire Áine Nic Dhonncha (d.1991) and the piping of Willie Clancy (d. 1973): their music is endlessly subtle and creative.

Did you have a dream(s) that you have lived it? Anymore is yet you would like to live in?

I have many dreams!

It’s great that you still remember Sacred Ryhthm Festival at the Nijo Castle in Kyoto. Would you join again if Sacred Bridge Foundation organized another cultural event?

Absolutely! We would love to take part in another such cultural event! Our trip to Kyoto was extraordinarily memorable, from so many different points of view…

Any messages you would like to say to the audience?

Trust your instincts. Don’t allow marketing men to convince you that black is white: beauty in music is life-enhancing and its absence saps the spirit.

…And any words of wisdom for Listen To The World?

No words of wisdom, I’m afraid! I will simply say that I love Listen to the World’s ethos and its ambition to present the real, the true and the beautiful in music.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

© 2014 - 2015 Old Bridge Music

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|